Tyrian Purple: The disgusting origins of the colour purple

Created from the desiccated glands of sea snails, the colour purple has nevertheless come to define royalty. Kelly Grovier looks at how the hue shook off its unexpected source.

Purple is a paradox, a contradiction of a colour. Associated since antiquity with regality, luxuriance, and the loftiness of intellectual and spiritual ideals, purple was, for many millennia, chiefly distilled from a dehydrated mucous gland of molluscs that lies just behind the rectum: the bottom of the bottom-feeders. That insalubrious process, undertaken since at least the 16th Century BC (and perhaps first in Phoenicia, a name that means, literally, ‘purple land’), was notoriously malodorous and required an impervious sniffer and a strong stomach. Though purple may have symbolised a higher order, it reeked of a lower ordure.

More like this:

It took tens of thousands of desiccated hypobranchial glands, wrenched from the calcified coils of spiny murex sea snails before being dried and boiled, to colour even a single small swatch of fabric, whose fibres, long after staining, retained the stench of the invertebrate’s marine excretions. Unlike other textile colours, whose lustre faded rapidly, Tyrian purple (so-called after the Phoenician city that honed its harvesting) only intensified with weathering and wear – a miraculous quality that commanded an exorbitant price, exceeding the pigment’s weight in precious metals.

So sought after was the colour (which eventually became the only shade in which priests and kings, emperors and magistrates would enrobe themselves), elaborate origin myths emerged to explain the dye’s predestined discovery. According to the 2nd-Century Greek grammarian Julius Pollux, purple was serendipitously stumbled across by the beachcombing dog of the demigod Heracles (the Roman god Hercules), who was on his way to canoodle with a nymph when his four-legged friend paused to gnaw on a sea snail on the seashore.

When the nymph saw the purple-stained muzzle of Heracles’ companion, she requested a garment of the same rich complexion. A portrayal of the scene, depicted around 1636 by the 17th-Century Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, Hercules’ Dog Discovers Purple Dye, shows the hunky mythological hero kneeling to pat the head of a hound that has just been chewing a snail’s anus. Though Rubens’ whimsical oil-on-panel painting erroneously depicts a spiral nautilus shell (rather than a prickly murex one), the work nevertheless corroborates the contention that purple, as a rancid dog’s-dinner of a hue, makes for an incongruous choice as a symbol of enduring majesty and power. This is a colour that pretends to transcend the vulgar vagaries of this world, all the while remaining mired in its muck.

Imperial cloth

In ancient Greece, the right to clad oneself in purgative purple was tightly controlled by legislation. The higher your social and political rank, the more extracted rectal mucus you could swaddle yourself in. According to the Roman historian Suetonius, King Ptolemy of Mauretania’s sartorial decision to cloak himself in purple on a visit to the Emperor Caligula, cost Ptolemy his life. Caligula interpreted the fashion statement as an act of imperial aggression and had his guest killed. Purple, it seems, was also to die for.

That the colour purple should have provoked the spilling of blood is perhaps unsurprising in the bruising light of its own haemoglobin glimmer. The nearer to the shade of clotted human blood that a manufacturer of the dye could manage to condense, the dearer his product. Given its invertebrate faecal inception, its putrid stench, and its proximity to the colour of corporeal distress, it is surprising that purple should ever have emerged as a symbol of worldly might, let alone otherworldly dominion.

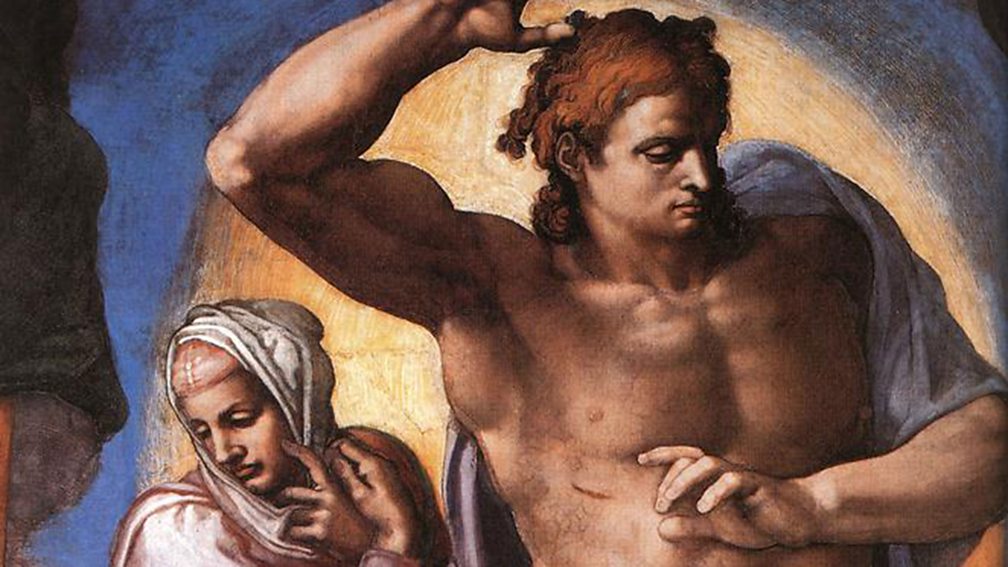

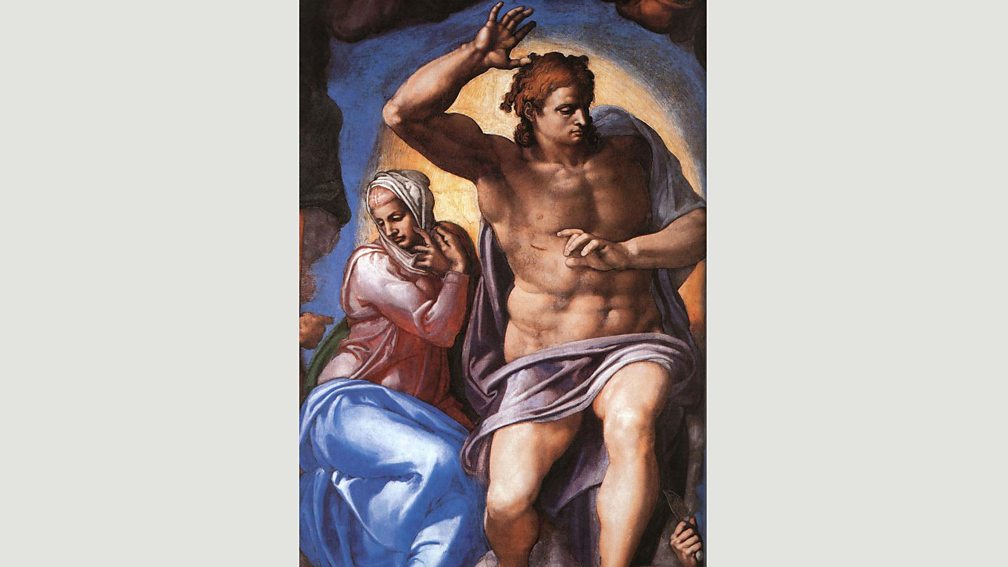

It was customary in Old Master depictions of the heavenly host, and of Mary and Christ himself (who is described in the Book of Mark as laden by his tormentors with purple clothes, lampooning his supposed status as ‘King of the Jews’), to transfer the raiments of royal authority to those taking charge of the hereafter. When seen through the lens of the dye’s unsavoury forging, the purple robe that seems forever to be slipping from the suspended physique of Christ in Michelangelo’s dramatic fresco The Last Judgment, which troubles the walls of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel, can be understood as another tawdry layer of worldly trappings that the Messiah’s Second Coming overcomes. This is the image of a purified humanity coming out of its compromised shell.

That teasing tension between noxious waste and exalted authority, between what’s visceral and virtuous, arguably seeps deep into the weave of every image that relies on the colour for its narrative power. Is it significant that when Raphael, elsewhere in the Vatican, imagines his famous soirée of ancient philosophers, The School of Athens, that his fresco’s central axis should be comprised of a purple-clad Leonardo da Vinci (in the role of Plato) and, just below him, scribbling on a block of marble, a purple-shirted Michelangelo (playing Heraclitus)? That the figures are, albeit in dress-up, the artist’s two most distinguished contemporaries, only amplifies their importance and companionability. Plato (who points upwards) was of course obsessed with all things endless, elevated, and ideal, while Heraclitus was famously forlorn by his focus on the fleetingness of things. Only the conflicted colour of purple – at once exquisite and excretory – could entwine the opposing dispositions into an equilibrium of eternal tension.

In time, the arduous task of disembowelling sea snails for their secret would give way to a more salubrious synthetic process. When, in 1856, the 18-year old aspiring British chemist William Henry Perkin accidentally discovered, while attempting to find a cure for malaria, an artificial residue that could rival the sheen of Tyrian Purple, he recognised his good fortune and seized it. Eventually settling on ‘mauveine’ (so-called after the Latin term for the mallow flower, Malva, which boasts a similar shade) as the trademarked name for his profitable invention, Perkin ignited a fashion sensation. Suddenly what had been for centuries an elite hue was widely available – demystifying its use.

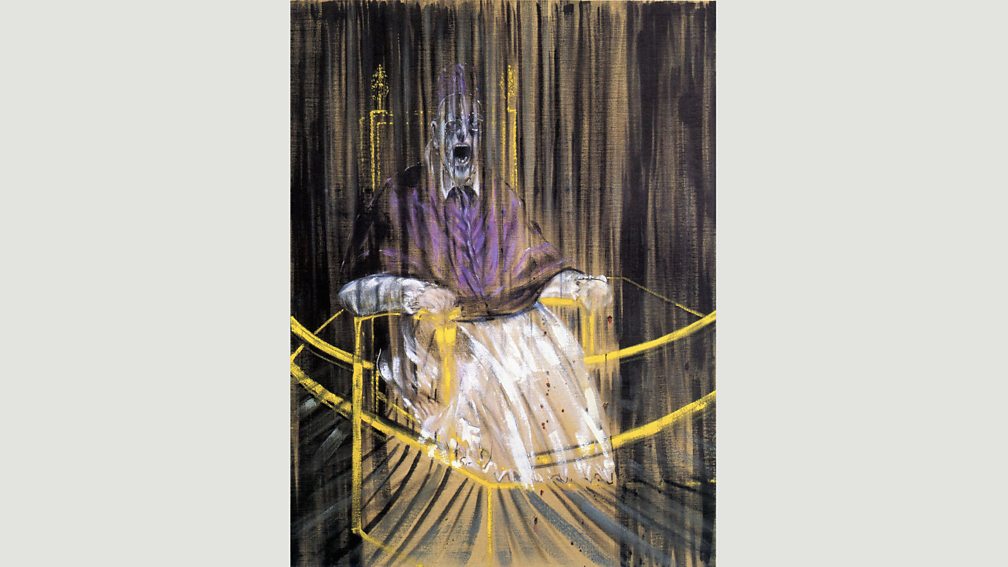

That’s not to say Tyrian Purple disappeared entirely from art or that its portrayal by painters suddenly ceased to intrigue or deepen the narratives of their work. When the Irish artist Francis Bacon resolved to reinvent in the 1950s Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X (1650) for a series of unsettling works popularly known as the ‘screaming popes’, he decided to recast the pontiff’s vestments not as scorching scarlet as his Spanish forebear had, but as pulsating purple. The result was as quietly alarming as the mute caterwaul that howls from his subject’s tortured lips.

Putting to one side the anachronism of Bacon’s vision (Pope Paul II had, five centuries earlier, declared that Tyrian Purple should be replaced by red for all official frocks), Bacon’s sizzling nudge towards violent violet is fitting, as if the Pope were undergoing the excruciating disgorgement of millions of molluscs over many millennia. Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X(1953) can be seen as purple’s silent scream into anguished oblivion – the last gasp of a gorgeously appalling colour.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.